"Did we forget how to rave?"—What being a "raver" means to me

On my personal definition of raving, how I came to it, and the many meanings of the word "raver"

As we walked away from where we’d tied up our jackets near the bar at the back of the converted basketball gym, my legs were still rubbery from the last bump. About seven of us stood at the back of the crowd, staring blankly at the pulsing light array hanging from the ceiling, waiting for one another to make the first move for what felt like entirely too long, until E’s booming voice cut the awkwardness with a question: “Did we forget how to rave?”

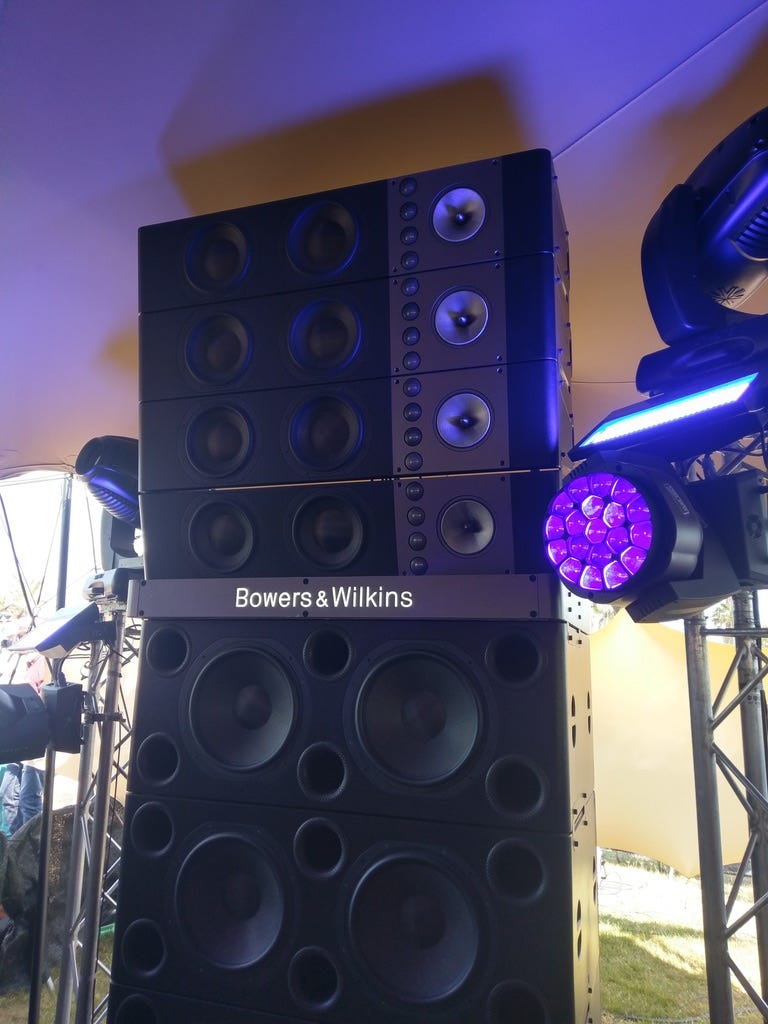

I started going to raves in 2016 after some friends and I decided on a lark to see the LCD Soundsystem reunion tour at Primavera Sound in Barcelona. Although the big stages were the main attraction, we found ourselves repeatedly drawn toward the Bowers and Wilkins DJ tent on the opposite side of the festival. This was no small thing, given it was separated from the rest of the festival by a 20-minute walk along a narrow footbridge stretching over a yacht marina. It was there, on the last night of the festival, that we first experienced Lena Willikens in all her glasses-wearing, chain-smoking resplendence.1

Although I had been to a few club nights thrown by friends of friends in the Portland electronic music scene and had seen Pitchfork-famous electronic music artists like Four Tet and Todd Terje perform in local venues and festivals, I’d never intentionally sought out a DJ-driven techno experience up to this point. I must confess, I found the whole concept a bit cringe at the time. Why would I pay money to see someone play someone else’s songs when I could see real live musicians perform their own art for the same price of admission? I wasn’t searching for an answer to this question when it came to me.

Willikens played for two hours, of which I only caught the latter half when our friends J and S texted the WhatsApp group saying that we could not afford to miss what was happening. Techno is easy to mock because it kind of all sounds the same—to the point where even a seasoned fan of the genre would have a hard time explaining in words what makes a “good” song better than a boring one. Although much of what Willikens played was technically techno, none of it could be mistaken for anything other than what it was. Synthesized melodies and distorted vocal samples layered over analog percussion, mixing into hip-hop-inspired breakbeats backed by wet and juicy acid riffs. If that sentence meant something to you, then you know why it hit. For everyone else, allow me to quote another friend who I recently discovered also had their first techno experience at Willikens’s hands: “I was like ‘Cool, my life is different now.’”

I cannot claim to be an expert on this topic, but for me, the line that divides partying from raving is painted by vulnerability. In the hands of an experienced DJ, the songs being played are unlikely to be familiar and you may never reencounter them thereafter. But none of that matters because it is really just about the vibe. The sensations that arise as sound meets body feel eternally familiar. All expectations and desires for what could be melt away as one becomes absorbed in the present moment, opening fully to the DJ. In this state, a dancer’s movements become an instinctual, involuntary reaction to the music. You could call it a trance, but this implies a directionality in the relationship between DJ and dancer that doesn’t quite capture the full truth. Although the selector controls the music, the dancer’s sustained attention is just as important a part of the equation. When all of this comes together among a critical mass of people on the same dancefloor, we are raving.

Raving is neither achievable, nor necessarily desired by any given combination of DJ, dancer, and party. Raving is not about trying to have a good time. It is not about blowing off some steam. It is not an excuse to get blasted on drugs. (Although it can consist of and often includes all of the above.) It is about being completely present in the moment as it is unfolding among others going through the same experience.

Fast forward to September 2023. I am at a summer camp in the Western Catskills with some 1500 other people attending an independent electronic music festival that I describe as homecoming for the New York rave scene. After what has already been an indescribably transcendent weekend, Lena Willikens and longtime collaborator Vladimir Ivkovic are preparing to take over the decks at 2AM—the second-to-last and prime timeslot of the entire festival. They were playing at the outdoor stage, situated in a clearing amongst the pine trees bordering the camp’s boating lake and tenting area. It was a clear night, which meant the air was cold, causing steam to rise from the lake. I was with a few members of our crew on the other side of the lake, waiting for someone to return from the bathroom when their set began. Even from across the water, we could sense that the vibe had shifted.

We carefully crossed the floating bridge to meet up with our friends, each wobbly step bringing us closer to our destiny. As we approached the opposite bank, I turned around from my position at the front of the group to snap a blurry picture of the world as I knew it, before what was about to transpire.

I could describe what happened next in words, but it wouldn’t do you any good. You had to have been there. Especially since the stage’s recording equipment had somehow failed to capture a single minute of the three-hour set. I later spoke with the tech in charge of running it and he lamented that power stoppages throughout the evening had led all the other set recordings to cut in and out, but this was the only one that completely disappeared into the ether. A couple of months later, I ran into Ivkovic at a different party and told him the news. “Good,” he responded. “I am glad the recording doesn’t exist.” He continued, saying something along these lines: People think they can stay home and listen to the stream and get the experience, but this is not true. You must make the effort, the same as all others involved. It is better when you contribute.

This year’s iteration of the homecoming festival felt different. In particular, my Friday night suffered from a failure to launch that no amount of changes to scenery or consumption habits could overcome. Finally, around 3AM, after a while spent wandering aimlessly alone, I found a group of my friends congregating by the fire pit outside the main stage—a children’s basketball gym that’s been lined with anti-fatigue mats across the court; LED beams, lasers, and industrial fans across the ceiling; and a Funktion One speaker stack looming in each corner. After a few minutes spent catching up, we decide it’s time to check out what’s happening inside.

Holding our jackets in our arms, we insert our earplugs and follow each other into the back of the crowd, taking in the pulsing lights, music, and bodies. Skee Mask is doing his thing, which means different things on different nights, but tonight, for now, it means relentlessly pounding techno—the kind that normies make fun of for all sounding the same. I can tell it’s the good kind, but can’t tell you why. However, it’s too quiet in the back. I make gestures towards the bar, where we’ll be able to leave our jackets, freeing us to move into the mix.

We now find ourselves returning to the beginning of this story and it’s time to face the question: “Did we forget how to rave?”

Chortling at the thought, I snapped out of whatever funk had overtaken me and led our little crew towards the front right of the room, where I knew the lights to be dim and the sound overpowering. As we drew closer, the bassline became louder, became felt, became embodied. We reached a pocket of space just a few feet from the speakers and, in a literal sense, got to work.

Closing my eyes, I see a gooey globe of light, pulsating and shedding trails of color in time to the music as my head begins nodding along. My legs hone in on the same frequency, bouncing from foot to foot in time with the bassline, hips swinging in tow. A synthetic snare crashes into the mix and my fists are pumping to their rhythm as if punching a speedbag. The goey globe collapses in on itself, leaving a gaping hole in its wake and I jump in after it, digging deeper and deeper with no bottom in sight. Each beat dredges out more sludge, more dirt, clearing the path for more digging, like snaking the drain of my soul. More bouncing, more bobbing, more punching. The song changes seamlessly every 2-4 minutes and my movements adjust accordingly. My closed eyes can’t see if others are doing the same, but they don’t need to because I can feel the vibe is all around me. We are raving.

My friend J has described raving as being coextensive with meditating, but I never fully grasped the truth in that statement until this weekend. Above all, they share the characteristic of having a goal that is achievable only through letting go of your desire to achieve it. Our only role is to be present and aware so that we can recognize it when it comes. This is easier to do when we put ourselves in a semi-monastic environment designed to facilitate the experience. Moreover, there are many different expressions of this goal that can only be achieved through different kinds of practice. The aforementioned description of raving is just one among many that I’ve personally experienced. It just happens to be the kind that I feel most prepared to articulate. It is based on my personal experiences and not meant to be prescriptive of how others might feel. That said, allow me to talk some shit.

Raving is as much about hedonism and feeling good as meditation is about becoming a more productive member of a capitalist society. Which is to say, not at all. This is the source of the tension that exists between the identity of “raver” by those who practice raving and the popular connotation of the label in the broader culture. This is not to imply that a “real” raver holds any moral superiority over someone who macrodoses molly at Electric Zoo, but only one of these types of people could do what they do while also being the CEO of Goldman Sachs.

Now to finally answer E’s question: Yes. I forgot how to rave.

Part of this had to do with the fact that I’m now a meditator. While I am more cognizant of my awareness when I am aware, this has ironically made it more difficult to actually be aware because there’s this extra layer of being aware that I am not currently aware that needs to be disentangled before I can become aware. Part of this had to do with the fact that last year’s festival was so indescribably brilliant that it was difficult not to cast aspersions towards every little difference I encountered. Things like expanding the capacity of the outdoor stage and changing the orientation of the lights in the indoor stage felt like an affront to my memory of the perfect weekend I was not having this year—even though it obviously had nothing to do with me. But in the end, if the company and music are good, and your mind is set just right, none of that matters. You start again as if you’d never left.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription. Nothing brings me more satisfaction than writing these pieces and your monetary support keeps the project free to read for everyone.

There’s no recording of that particular set, but I imagine it was pretty similar to this one from Dekmantel later that summer, which is really good.

to the point where even a seasoned fan of the genre would have a hard time explaining in words what makes a “good” song better than a boring one. I'll tell you what makes a good song better than another - Depends on when your E peaks, that's always the best track of the night.

I thought this was a really insightful take on this matter. I would deeply appreciate if you check out my similar post on nihilism as a teenager and what life entails for those who are lost!